We have come a long way. But we have a long way to go. Hemant Jalan, President and Managing Director, Indigo Paints

Image: Varun Kulkarni for Forbes India

Yesou want to start a business. To the right? And your heart says you’re not cut out for a job. Alright, so before you jump in, why don’t you ask a question and see if you’re fit for entrepreneurship? “Step back 5 minutes,” urges Hemant Jalan, 63, founder of Indigo Paints, to all aspirants regardless of age. “Now think, if this business goes horribly wrong, how far will it set you back?” he asks. Remember, he stresses, that business isn’t just going bad. “It’s going horribly wrong.”

In 1985, a young Jalan – in his late twenties – did not ask himself this question. In fact, it never crossed his mind. “I had a fiery confidence and I had achieved everything so far,” he recalls. After completing his BTech in Chemical Engineering at IIT-Kanpur, Jalan pursued his Masters at Stanford University and an MBA at Chicago Booth School of Business. With his degrees and knowledge, he established a few small and medium chemical manufacturing enterprises in Patna. Twenty-something, he believes, is more likely the expected age to become a founder.

A decade later, in 1995, he encountered technical problems in his manufacturing equipment. “The biggest unit I had set up completely failed. It was a big fiasco,” he says. The setback was massive. Jalan was driven to the brink of bankruptcy and was forced to sell all of his assets, including his house and car. “I had nothing left”, he regrets, adding that the trauma was not over; he still owed a lot of money to the banks.

As his entrepreneurial dream turned into a nightmare, the 38-year-old started looking for a job. “To make the family work, forgetting about entrepreneurship was the only sensible thing to do,” he says, justifying his move. In early 1996, he joined Sterlite Industries and headed their copper smelting division in Tuticorin, Tamil Nadu. He worked for three years. “It was a great experience. I learned a lot,” he says, adding that professionally he was quite happy and satisfied.

The problem, however, was with his heart. He was panting for an independent journey. “It wasn’t in my DNA to take instructions from someone,” he says, alluding to his time as an employee who came after a decade of remaining fiercely free as a master. Sometimes his work made him feel a bit smothered. In early 1999 he resigned and faced an uncertain future. What mattered most to him was the voice of his heart that kept reminding him that he wasn’t cut out for a job.

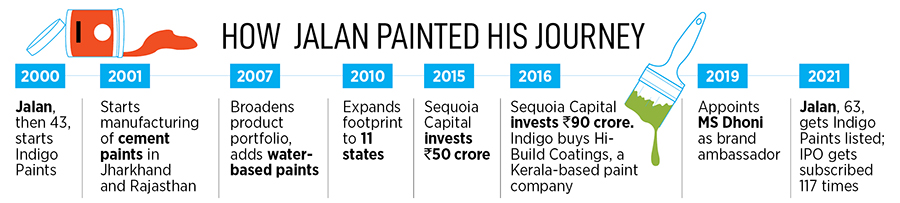

Then he moved to Pune, Maharashtra, and worked as a management consultant for a year. The short stint helped him gather his thoughts, discover that he still had a small working chemical unit in Patna, and decide on his future. In 2000, he launched Indigo Paints. “I had no idea where this journey would take me,” he admits.

Then he moved to Pune, Maharashtra, and worked as a management consultant for a year. The short stint helped him gather his thoughts, discover that he still had a small working chemical unit in Patna, and decide on his future. In 2000, he launched Indigo Paints. “I had no idea where this journey would take me,” he admits.

He remained bold and took the leap. Jalan was 43, had two children – her daughter was 17 and her son 13 – and didn’t have enough to invest in the business. “I started with less than a lakh,” he says, adding that he knows 43 is not the ideal age to restart. “Age mattered because of the previous failure. Starting over was a huge risk,” he recalls.

Fast forward to 2021. Jalan is 63 now; Indigo Paints is two decades old; it listed earlier this year and is now trading around 50% above the offer price; it is also the fifth largest brand of decorative paints in India and recorded revenue of ₹723.32 crore and Ebitda of ₹122.52 crore for FY21. “I just followed my heart,” he said. If your heart, he points out, says you can do it, then you can.

During the early years, on several occasions, Jalan’s heart was in his mouth. The paint industry was dominated by the big boys – Asian Paints, Berger and Nerolac. Taking the biggies head-on would have been disastrous. Jalan made a handful of clever moves. First, he stayed away from big, congested cities. Second, it has found its way into differentiated products. And finally, it tapped into Tier 3 markets and beyond. The reason was simple. Brand penetration is easier and dealers have a greater ability to influence customer buying decisions.

What also helped Jalan immensely was his experience during the Sterlite days. The biggest learning was to keep fixed costs to an absolute minimum and keep everything variable as much as possible. “When we started, we didn’t invest in land, buildings or anything,” he recalls. The brave founder identified a closed industrial unit, just set up a skeleton factory and low-cost machinery, and started manufacturing. The idea was to test the waters and take calculated steps and risks. “If things went wrong, we knew we could easily get back on without too much damage,” he says, justifying his sure play.

The seasoned entrepreneur also decided to play by the rules. “We made sure to make a net profit every month and never incur a loss,” he says. The move made sense again. Apart from instilling fiscal discipline, Jalan lacked the comforts of venture capital at first. Sometimes the monthly profit was as low as ₹2,000, but that didn’t matter. “We weren’t bleeding. That’s what mattered most,” he says, adding that while staying frugal might have pushed Indigo Paints back in terms of speed, it ensured the foundations were rock solid. It also meant that Jalan didn’t have to think about the fear of failure as he continuously covered his ground.

After six years, for Jalan and Indigo Paints, it was not a question of survival. It was about picking up the pace. “It took us 10 years before we could start paying salaries on time,” he says. The brash confidence of the 1920s, he points out, is now tempered by heavy doses of reality.

After six years, for Jalan and Indigo Paints, it was not a question of survival. It was about picking up the pace. “It took us 10 years before we could start paying salaries on time,” he says. The brash confidence of the 1920s, he points out, is now tempered by heavy doses of reality.

“I couldn’t afford to make a mistake for the second time,” he said. He knew the cost of failure was incalculable at his age. The leisurely pace of Indigo Paints was also due to another ground truth. Jalan explains. When you have kids growing up, going to college, your perspective changes. “You can’t put their future on the line,” he says. The hope of a promising future kept him going.

In 2014, 14 years after the start of its second run, the turning point came. Sequoia Capital spotted the company and backed the founder. “It completely changed the game for us,” says Jalan, who now had the money to advertise. The founder, however, did not paint the city red. The reason still emanated from his past. “Now we understand the value of money much better,” he says, explaining how he was different from a wave of young entrepreneurs who built their businesses around collecting and burning money. “Most of the money invested by Sequoia is still intact,” he says. While to an outsider this might seem insane, to Jalan it was prudent. The money, he says, acted as a buffer and allowed him to take bolder risks. “We had our backs covered,” he smiles.

Cut to 2021. Jalan feels he had a tough but satisfying journey. Ask him how he managed to put his disastrous past behind him and muster the courage to start over in his 40s, and pat comes a one-word answer: Future. “If you keep thinking and brooding over your failures, then you’re dead,” he says. Starting late in life, he points out, is not a problem. He offers an example of Falguni Nayar from Nykaa. Imagine how difficult it would have been for her to start as a founder, since she didn’t even have entrepreneurial experience, he wonders. “In my case, I’ve been an entrepreneur most of my life, except for three years,” he says, adding that his failure shaped his success.

A big failure, he believes, is the greatest learning and a huge blessing. When that happens, it’s like the end of the world. But later, when you do some introspection, you can see how hard lessons pave the way for future success. One might be justified in accusatory circumstances, but hard knocks are blessings in disguise. “It helped me make more good decisions than bad ones at Indigo,” he says.

A big failure, he believes, is the greatest learning and a huge blessing. When that happens, it’s like the end of the world. But later, when you do some introspection, you can see how hard lessons pave the way for future success. One might be justified in accusatory circumstances, but hard knocks are blessings in disguise. “It helped me make more good decisions than bad ones at Indigo,” he says.

So what does it take to become an entrepreneur? Jalan returns to his starting point and answers the question he asked all seekers: “What if things go wrong?” If the setback, he points out, is something that can be painfully endured and set back a few years, then take the leap. But if you’re putting it all on the line and the bet can shave one off, then it’s probably not a good idea, he said, cautiously.

“Weigh the stakes involved, and if your heart still says you can do it, then go ahead and do it,” he says. “Nothing is more satisfying than being a successful entrepreneur,” says the seasoned founder who is always hungry to add more color to his business.

Click here to see Forbes India’s full coverage of the Covid-19 situation and its impact on life, business and economy

Discover our end of season subscription discounts with an absolutely free Moneycontrol pro subscription. Use code EOSO2021. Click here for more details.

(This story appears in the December 17, 2021 issue of Forbes India. To visit our archive, click here.)